“You have to have grit to hunt elk … I’ll do whatever it takes to get an elk.”

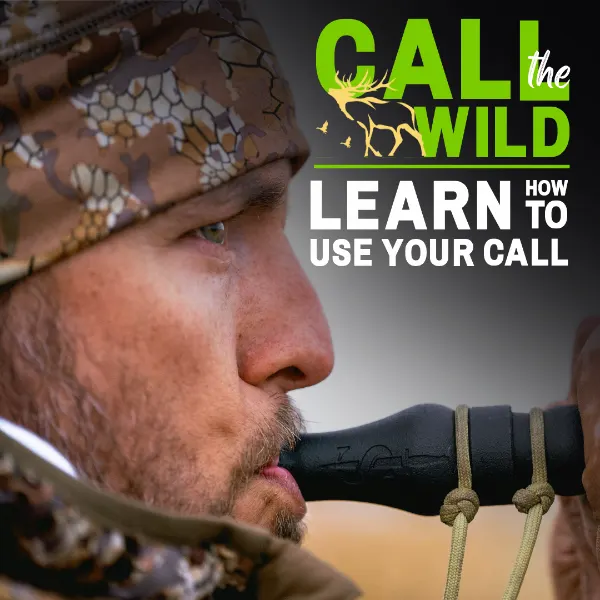

Overview

RMEF World Elk Calling Content finalist Joe McCarthy knows a thing or two about bugling for bulls. He’s been hunting elk along the ridgetops and drainages of Idaho’s mountains for decades.

Listen to the full podcast above or watch the conversation unfold on Slayer Calls YouTube channel.

McCarthy shares his expertise on reading the language and emotion of bulls, cows and calves, from mews and chirps to barks and bugles. For new hunters, McCarthy explains the classic rules of archery elk hunting: choosing your location, calling, and staying downwind. But those rules? They’re all meant to be broken, if it means you’ll be eating elk steaks by the end of the hunt.

In this episode of The Slayer Hunting Podcast, host Tommy Sessions talks with Slayer Calls CEO Bill Ayer, Slayer PRO Tanner Hardy and Slayer product innovation lead McCarthy about the language of elk and the secrets of successful bow hunts.

Elk hunting articles:

– 7 tips for your first archery elk hunt

– How to choose your first elk call

– E-scout to maximize success on out-of-state elk hunts

– Star of The Wild Race lands a 6×8 bull on her first elk hunt

Slayer calls related to this episode:

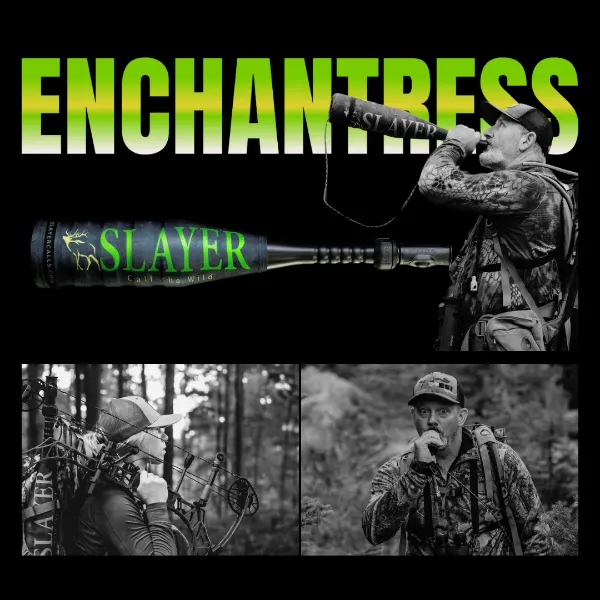

– Enchantress push button call

—

What was it like the first time an elk responded to your call? Drop us a line at [email protected] to share.

Thanks for listening! We’d love to have you back, so subscribe to The Slayer Hunting Podcast to make sure you don’t miss an episode. Listen to The Slayer Hunting Podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify and Google Podcasts.

Connect with us on Instagram and Facebook and subscribe to our YouTube channel to feed your obsession between episodes.

If you’d like to support Slayer Calls, 10% of each purchase goes to organizations that protect the environment and wildlife, support conservation efforts and preserve America’s hunting heritage. Grab a gift card for the hunters in your life to celebrate everything from birthdays to holidays to the start of duck season.

Read the Full Transcript Below

Tommy Sessions (00:00:00):

All right everybody. Welcome to the Slayer Podcast. I’m Tommy Sessions. This week we’ve got Tanner Hardy and as I like to call him, the professor, Joe McCarthy. As last week, you guys may have known or watched or listened. Joe McCarthy was on there and we talked to him at a huge broad spectrum of elk hunting with the setup of your season to some equipment and so on and so forth. Today we’re going to go a little bit more into in depth of actual calling.

Bill Ayer (00:00:35):

Cool. Yeah, calling, I think in the field calling, what all the different sounds that you’re hearing, what that means, situations, you do a location bugle, you hear a bull answer you back, what do you do? So I think this would be great for somebody new who’s getting into it. Even for myself who’s been hunting for elk for 20 years, I’m definitely going to learn something from the professor here.

Tanner Hardy (00:00:56):

I’m sure I’ll have lots of questions.

Tommy Sessions (00:00:59):

And here I am. Tanner just told me we can’t forget to introduce the owner, the founder of Slayer Calls, Bill. So as you just heard Bill talk a little bit, but sorry about that Bill.

Bill Ayer (00:01:12):

Yeah, no problem. And I think it’d be good to introduce everybody. Just there’s a lot of different backgrounds here and everybody might not know. So Tanner, maybe you could start your background. I think you’re new to elk hunting.

Tanner Hardy (00:01:24):

Yeah, yeah. Very new. Or as you could say, this will be my first year elk hunting. I’ve always been a big mule deer hunter, spent a lot of time in the hills chasing bucks around, but never had the opportunity or anybody that I knew that I wanted to get into elk hunting with. It was always just some people elk hunted. I chased mule deer.

Tommy Sessions (00:01:46):

So what brought you into elk hunting? Because I know a lot of people like mule deer hunters, they will not touch, they won’t even go buy an elk tag. They hate it. Like me, I’m an elk hunter. I won’t go buy a mule deer tag. I could care less. It’s just going to interrupt my elk hunt.

Tanner Hardy (00:02:02):

Mostly archery shooting bows. I was never into bows either. It was always rifles for me. But my brother-in-law has been super into bows and I shot his little bit and I was impressively good he said for never shooting a bow and it wasn’t fair. So I was like, maybe I’ll buy a bow and start shooting. So I bought a bow and started shooting. And then I’ve been with elk, with Bill, doing the duck hall thing for a long time and I know he’s into the elk. And so just, between my brother-in-law and Bill, always talking about elk hunting got me a little curious. And after buying that bow and shooting a little bit, I decided that it would be a pretty fun thing to chase around the bull and get him screaming at me. I got ducks all the time, but it’s not quite the same intensity.

Bill Ayer (00:02:45):

Yeah, I remember asking Tanner, I’m like, “Hey, do you elk hunting?” He’s like, “No.” I’m like, “Dude, you’re born and raised in Idaho. How do you not?” I mean, he goes to deer camp every year with his family in two weeks. I mean-

Tanner Hardy (00:02:56):

That was it. I mean, it was 10 days in the hills chasing mule deer and that was vacation for the year.

Tommy Sessions (00:03:02):

Well, I don’t, back to your comment about how did you grew up in Idaho and you don’t elk hunt. I did the same thing and honestly I didn’t elk hunt until, oh man, it’s probably 10 years ago now, I think. The reason that the Arc angels named after Jesse Hill, he was my hunting buddy and he got me into it. And that was like I say about 10 years ago. And my motto was always, I only get a chance to shoot one animal. I waterfowl hunt so I could shoot a lot of animals and I could be out in the field a lot more until I started hearing that one bull screaming. And then from then it’s been an elk hunter by far. And then Joe McCarthy, the professor. So what have we got Joe? I mean, you’re-

Joe McCarthy (00:03:45):

I don’t know.

Tanner Hardy (00:03:47):

Joe’s born and raised Idaho too, right?

Joe McCarthy (00:03:49):

So I’m fourth generation Idaho, I guess. Cody would be fifth and Sage would be sixth. So actually my great-grandparents came out here prior to Idaho, being a state homesteaded basically grew up, my grandmother grew up, I guess subsistence hunting for deer back in those days. Didn’t even have elk in Idaho. They hadn’t come through really until after 1910. But my dad was an outfitter growing up, hunted waterfowl mostly, and then got into fishing salmon, steelhead, sturgeon. I like everything, I will do anything to stay out in the field. I will catch crappy. I will go hunt elk, I’ll catch sturgeon, I’ll hunt ducks. There is nothing I will not do in the field. I want try to be out in the field as many days as I can a year. The elk thing though is probably the number one deal in my life.

(00:04:48):

I grew up calling ducks, which I think really helped me learn how to call elk. But that interaction you have with calling ducks, hitting that note and watching those wings turn and come in, it’s the same thing as calling that, you lay a bugle out and then all of a sudden you see that elk coming in at 10 yards or something and they’re screaming at you and you can feel the bugle, you can feel the grunt against your body. It’s just a crazy experience. And once that happened to me, I was pretty much in. And so I’ve hunted elk pretty much my whole adult life. Bugling as much as I can. I’ve primarily hunted with a bow. I have hunted with a rifle and a muzzle-loader too. But primarily I like to hunt with my bow. That’s probably my favorite weapon. And it’s just the interaction, the interaction you get.

(00:05:41):

There’s just nothing else. It’s such a big animal, majestic animal. There’s a challenge to it. Like you said, the duck hunting thing, it’s fun. I go out there, eat a sandwich, shoot half a dozen ducks and have a good day, watch the sun come up over the water, steam, mist. I take pictures of all that kind of stuff. I love that stuff. But man, there’s something about going out in the high country and you hear that bugle at a distance. It’s challenging because it taxes you physically. I mean it taxes you mentally. It taxes you pretty much in any way you can. I think that’s why we named the calls the way way we did with the fortitude and things like that. I mean, that’s a part of elk hunting. You have to have grit to hunt elk. It’s just not something you go out and I’m just going to do.

Tommy Sessions (00:06:31):

Absolutely. I think if you look at elk hunters in general, it is, like you said, the calls, the fortitude. I mean, it’s such a piece of your heart that goes into it. And like we talked about a while ago, it’s emotion. Your emotion goes into it, into the calling, into the hunting. You could be the biggest guy that you ever know, the biggest, strongest, toughest, biggest dude or gal or whatever. And you shoot an elk after a hard season or even a hard calling or whatever. And even the toughest people break down and cry, but it’s just pure emotion. And then you get this animal down that’s just like you said, it’s majestic. And there’s nothing like having a monster or even a rag horn, it doesn’t matter. But bull bugling screaming at 20, 30 yards, and I can only describe it as a thunder, the rumble of a thunder like bugle. It’s hard to explain, but it reverberates and it vibrates your chest and it’s awesome.

Bill Ayer (00:07:38):

Yeah. It’s humbling too because I always consider myself in decent shape and then when you pack an elk out, it humbles you really fast. Being big and strong is there’s an advantage to putting weight on your back, but you’re also taking a lot of weight uphill yourself and the elk and it’s so, it equalizes a lot of different people sizes and strengths and things like that. It’s pretty humbling.

Tommy Sessions (00:08:02):

Absolutely. So like we talked about, we are going to talk about calling today. We talked about scouting last time we were with you, Joe. And so now let’s fast-forward it here. We’re into September and we’ve already scouted everywhere we want to go. And so we’re now hiked out into the mountains, set up the scene we’re at, we’re hiked out in the mountains, we’re on that north face slope, we’re on that ridge top or whatever. We’ve scouted. Let’s just go a scenario of what do you do? I mean you get out there, we’re going to try to get this out to the beginner. That’s what we’re really working on. And honestly, I learned a lot from last podcast. We’re going to learn a ton from this one too.

Joe McCarthy (00:08:45):

I think at first it’s really listening to what the elk is telling you because you’re throwing stuff out when you’re bugling to see what sticks. But ultimately it’s what does he say to you? What does the cow say to you? You’re listening for all that and then you’re going to make some kind of decision based on that. I think people simplify things as far as what elk sounds they make, I mean people say, well, they bugle, they grunt and then they cal call. Well, cal calls are muse and chirps. You got barks. As far as bugling goes, there’s locate bugles, there’s display bugles and there’s all these, everybody wants to name them. And I’m okay with that because I think it has, there is a purpose to that. But all those things, the display bugle, a moan, a check bugle, the challenge bugle, all these different things to say, the reality is it’s emotion.

(00:09:41):

It’s all about emotion and it’s reading that emotion no different than the duck calling. And this is where I say the duck calling taught me how to listen to elk because you’re watching for the wing beat to chain. When you highball a duck at a quarter mile, if he just gives you the wing beats that just keep on going, you got to do something different. If those wings twitch, then you’ve done something. And so that’s the listening to that elk. So when you throw out that, I typically start mild in my hunting so I can get out whether I’ve walked a ridge or just getting out of my car or whatever I’m doing. And to be honest, when I start, I walk, I ride, I do everything.

(00:10:27):

There’s nothing I won’t do to hunt elk. So I mean if people want us talk about car hunting or truck hunting, road hunting, you know what, I know people that kill a lot of elk off the road, but I’ve also walked in seven miles to go get an elk as well. But the technique is always the same. I try to work ridges, I try to work areas where I can cover a lot of ground with my bugle. I typically start timid a little bit, throw out a few chirps, chirps that cow is just talking around the water cooler kind of thing. They’re just all grouped up and they’re just-

Tommy Sessions (00:11:02):

Well, can you give us an example of it?

Joe McCarthy (00:11:13):

… and that’s just, they’re just hanging out together. They’re just making some noises. Muse are more drawn out and that’s where they’re saying, hey, come here. It’s like your kid saying, hey, come over here. That’s the mue or the chirp. And then it’s like they’re not responding to you. So you’re like, get over here, that’s the mue. That’s the longer [inaudible 00:11:36], which is going to be a little longer.

Tommy Sessions (00:11:37):

And are they talking, a cow talking to another cow or a cow talking to maybe the whole herd and a spike and a rag horns included in that herd.

Joe McCarthy (00:11:45):

I think in a herd scenario you’ll get cows and bulls. Now they’ll all chirp and make noises. They’re just checking each other out. Just kind of like, hey, just that hanging out and visiting so to speak. But when the cow loses her calf. More pleading. It’s like in duck calling that plead call instead of that… It’s that pleading that call. And so you’re doing that. Now I will say a lot of people really like cow calling. I think there’s a lot of ways we can hunt elk and everybody’s got their own opinions. Personally I think elk talk to each other in a calf type manner all year long. And I think you can screw up more making cow sounds than you do making bugles. Elk get very hoarse. They bugle a lot.

(00:12:50):

A elk is not going to win a elk calling contest by September 16th. He ain’t going to do it because his voice is shot. And so you can screw up in bugling and you can still get away with it. But I think with cow calling, I think the bar is a lot higher. So you have to be a lot better at your cow calling. Not that you don’t do it, but I think you need to be better at it. I don’t want… Joel Turner, he’s another retired now. I was a retired law enforcement officer in Idaho. Joel Turner’s retired law enforcement officer out of Portland and he won the pro class bugling thing 10 years ago, something like that. But he’s talks about hunting over in Oregon where he will throw out almost all calf chirping because it’s not aggressive. It’s very quick. It’s very short. Those little chirps.

(00:13:53):

They’re not as aggressive. They’re easy, they’re short, they’re not drawing out where you can get a bunch of weird stuff happening. But a bull will respond to that. A cow will respond to that because it’s kind of like the little kid. I mean they’re making noise and they’re checking them out versus hearing something that’s like, what the heck is that? Almost everything will respond to that calf. And so he will throw a lot of that stuff out. So I guess what I’m getting at is I will throw some of that stuff out in the very beginning. I’ll throw out some calf calls, maybe throw out a cow call or two. If you can get a bull to respond to a cow call from the get-go, you got good things were happening because that bull is going and he’s hot, in my opinion.

(00:14:37):

If that’s what’s getting you going, that’s what’s getting him going. I’ll start with that though, just to break the ice. I don’t want to necessarily go out into a big open area and just throw a bugle out there and just shake everything up. I want to step it in, throw a few little cow calls in there, step up my intensity a little bit and then I’ll throw out that location bugle. And that location bugle, it can be really short but high. Just something like that. Totally non-intimidating. Just the high note. The thing about a high note too is high note travels across, it travels a long ways and you’ll hear that high note a long ways away where you don’t necessarily hear all that base. And so I think that it sends that note out to the canyon. It lets try to figure out who’s in the neighborhood so to speak. And then I’ll slowly start ramping it up from there.

(00:15:35):

If I get something to respond then, then I’m done. I will move and cut ground. If I don’t, I keep ramping up things until I go into a challenge bugle, I’ll go into more, whoever I’m hunting with will often bugle back and forth, we’ll separate maybe two, 300 yards apart and call back and forth to each other, like we’re cows and calves are herd two bulls getting together. That’ll often incite something. Even if you just have one going bull might be like, oh whatever. But you get two elk going then he is like, well something’s going on up there and now you got to fight. Maybe it’s just being down at sixth and main. It’s like, oh, shit. I shouldn’t say that word. It’s like, hey, there’s a fight. And so everybody gathers around it. So that brings people people in. It also brings elk in.

(00:16:26):

So that going back and forth kind of thing, it can make things happen. If nothing happens, and I don’t necessarily just go bailing off down into the draw. I want to cover ground and if you’re going low and going into a bunch of timber or something, you’re going to move slow. I want to cover ground. And the reality is that high note now depending where you’re at, how far it covers, but in Idaho in a lot of high places you could be going cover half mile, mile and get that to go. Now if it’s a heavily hunted area, a bull might not actually respond to that at a distance because they’re used to people and whatever making noises and they may be something you have to start closing the distance on them. So I’ll move and I’ll keep bugling along the way and at some point you’re going to you get that reaction and then you read that and then go after it.

Tommy Sessions (00:17:18):

So I’ve always been taught and I’ve always had the theory of three-quarter mountain and I know you say you like hunting on the ridge tops and stuff like that. And I’ll definitely hunt the ridge tops, but I’ve had times too where you bugle off the ridge top, down in and nothing and all of a sudden you go a hundred yards down the mountain and you bugle again and they’re just fired off.

Joe McCarthy (00:17:39):

Yeah, you break the bubble.

Tommy Sessions (00:17:41):

Yeah. It seems like maybe they’ve either had hunting pressure and that’s something else we want to talk about is a little bit of hunting pressure and calling. But they’ve had hunting pressure and you just crest that bubble or whatever and you call a little bit, you’re distinguishing yourself from another hunter.

Joe McCarthy (00:17:58):

If I know there’s elk in an area, then that I will, I guess vary from what you’re doing. There’s nothing I won’t break. I’ll break every rule I ever said. I’ll do whatever it takes to get an elk.

Tommy Sessions (00:18:09):

There are no rules in elk hunting. Other than laws.

Joe McCarthy (00:18:13):

I think when you first enter an area, you don’t necessarily know where things are at. I will look at drainages that have water. I’ll look for areas where there’s maybe a bench where you might have some kind of a wallow in that area. I might go down. I like the idea of a three-quarter mountain. Because it seems like elk sit at three-quarter mountain and it’s far enough that it’s hard to get from the bottom up. But they can get ahold of you on the way down and they can move down to the bottom pretty easily. So I think that three quarter mountain thing is a good idea. I will get in, if you know they’re there, I will close the distance and try to call, change my calling a little bit to be, if they’re not bugling right away, I’m going to start changing, maybe doing more moans, more just regular stuff… something like that.

(00:19:08):

Maybe just even the little grunts… something like that. Just throwing out a little bit to see if I can get some kind of reaction. To sneak in on an elk is really hard. I mean, you got especially a decent bull who’s got cows around him, he got eyeballs everywhere. Kind of want him to make some commitment move. Like you said, breaking the bubble is great if you can do that, if you know where they’re at. But initially, if you don’t know where they’re at, for me covering ground and I want to cover ground-

Tanner Hardy (00:19:43):

So in the scenario that you’re on the ridge top and you’re calling, you’ve talked about what you would do to try to get a bull to respond. When you get him to respond, what’s your next step from on the ridge top?

Joe McCarthy (00:19:53):

Wind. Check the wind. Mornings, obviously mornings you’re going to have downward thermals. In the evenings or afternoons you’re going to have upward thermals. Then you’re going to have your actual prevailing winds. So from where you’re at to where he’s at, trying to figure out which way is going to be the winds. And I will look at draws because especially on top of a ridge, you’re going to have a prevailing wind. That’s what you’re going to feel. And you’re going to be like, okay, well I got right to left wind, I’m going to go down to the left.

(00:20:22):

But if I see down there that there’s a draw that’s going… Once I get over that hill, there’s going to be a thermal in the morning going down, which I don’t want to be in the same draw as him. I want to be the one to prevailing wind, downwind. And I’ll move down that draw in reading those draws, trying to figure out which way that, I mean it’s just like water. If you were to pour a million gallons of water down the canyon, how’s that water going to flow? And so I’m going to look at that and then get down wind of him. I want to cut the distance in half, maybe even three quarters.

Tanner Hardy (00:20:53):

Before you make another sound?

Joe McCarthy (00:20:55):

Before I make another sound.

Bill Ayer (00:20:56):

Yeah. So say you hear him down in the draw 600, 700 yards, you’re going to try to get down there about 300 yards downwind from him?

Joe McCarthy (00:21:04):

Something like that. And again, I’m going to start that whole scenario all back over. Start light, work it in, see what he does. And sometimes you’re moving down like that and they don’t, I mean they’ve made their location bugle or whatever bugle they gave you and they’re like, I gave it to you. I’m not giving it again.

Tanner Hardy (00:21:23):

I know a lot of people talk about elk aren’t quiet and especially if they’re just milling through, they’re not doing anything in particular. They’re walking and breaking brush, raking, whatever. When you’re moving to your spot that you’re going to cut it in half, are you being quiet? Are you just tromping down there?

Joe McCarthy (00:21:41):

I am. I’m going out of my way to knock stuff over, stepping on stuff, jumping over stuff. I don’t want to have a lot of, if you’re clothing, you wear a bunch of nylon gear, you got a bunch of stuff like that that’s on you, that’s making a bunch of weird sounds that’s different. But the clothing I wear, I try to make it as soft as I can, but I will make sounds. And I have Brie, Cody’s wife, we moved in on a bull a couple of years ago, moved in on, she was working in deep brush, a lot older. And she just couldn’t get a shot because she’s not really tall enough to be able to get up and shoot.

(00:22:15):

And then so we just said down, we’re done. We bailed out and we started just booking boogieing out. That elk chased us up and over the hill, it followed our foot tracks. And I think I’ve hunted the northern panhandle area where it’s really brushy and there’s times that that elk will be responding to me walking. They can hear me walking and they are coming to that sound. So yeah, I am not quiet, I just don’t want to have a bunch of metal sounds. I don’t want to have-

Bill Ayer (00:22:46):

Unnatural.

Joe McCarthy (00:22:46):

… unnatural sounds. Yeah,

Tommy Sessions (00:22:49):

But that’s a lot of with calling, obviously people maybe listening to this podcast are going to be disagreeing with us because they want to try to spot in stock or they want to try to do something else. So obviously this is going to maybe our style of hunting, because I’m the same as Joe is like, I don’t care if I sound like a herd of elephants going through there. As long as it doesn’t affect, it goes back to how the bull responds. If I’m running through the woods and he’s still pissed off and screaming, I’m going to stay running through the woods. But if I’m running through the woods and all of a sudden he shuts up and he doesn’t respond anymore, maybe it’s because of that or maybe it’s something else, but I’m trying to, at that point it’s-

Tanner Hardy (00:23:30):

You’re trying to feed off what those actions are telling you.

Joe McCarthy (00:23:33):

And I think listening to the elk talk, listening to them, are they just throwing up that non-aggressive high tone? Are they just throwing that out saying, hey, this is where I mim? Or are they getting pissed? And I will mimic that madness. Raking. It’s probably the most overlooked thing you can do. But raking a tree is sometimes when nothing goes, you rake a tree and everything goes. It’s because that raking a tree is a display thing that at bulls saying, hey, I’m a big bad dude and I’m tearing up this tree and that other bull’s like, heck no, I’m going to come over there.

Bill Ayer (00:24:09):

So talk about that when nothing goes. So I think I know what you’re saying there. You get in and on a bull, you close a distance, you try all your different bugles, you’re moaning, you’re chuckling, you’re trying to piss him off and then all of a sudden he starts to go quiet on you. Then you start raking and that turns them back on.

Joe McCarthy (00:24:26):

It can. And I think it works a lot, especially you’ve got a workable bull. Not all bulls are going to be workable. Some just depends on their mood, but that raking is definitely going to do some things. I get worried when things shut up. Did I do something to move and catch wind? Elk will move. I will say this too, when I bugle, I bugle and move. I bugle and move. I don’t necessarily hang in one place too long and I will work down. I’m constantly working downwind on things. And to the point of, I think people get frustrated because I’ll, like the orchestra there, and I’m like, no, we’re going to go down here and that means we have to walk down this hill a little ways and turn around and walk back up this hill. And it’s like, dang, that’s going to suck having to do that.

(00:25:13):

But by doing that I can get closer and not wind them. So I’m constantly, and I think by moving, you never know. I mean, that moving will changes animals and people sometimes sit too much in one spot calling. And face it, and if the elk’s sitting there and he’s hearing the same guy bugle in the same spot and he’s already responded to him once, I was like, I’ve already responded to you. What are you going to do about it? It’s that guy that sits two blocks away and he’s calling me a not a nice officer, and he’s saying that he wants to fight and he’s three blocks away. You start closing the distance, things change. And with an elk, I mean obviously we’re trying to get them to liven up and come after us. I think there’s some talk to sometimes being a smaller bull is good.

(00:26:08):

I think sometimes being a bigger bull is good. It’s matching that elk, cutting that elk off, taking away his manhood so to speak. When he bugles, cut him off, chop that bugle, just bugle right over the top of him and take away his manhood so to speak, and then try to fire him up that way. But working a bunch of different things in your basket, trying to figure out how to turn this animal on. And there are times, you know what, I was hunting with my wife up by elk river, and we’re pushing this elk and he’s bugling. I mean he continues to bugle, but he’s keeping that distance. He’s pushing his cows. You could hear him doing that roundup, that roundup thing, that moan… that kind of thing. They’ll do that. And when they’re rounding up their cows and they’re pushing and we just kept dogging them, just kept dogging him and just kept being that little kid in the background just kept nipping at him.

Bill Ayer (00:27:07):

Little ankle biter.

Joe McCarthy (00:27:08):

Little ankle biter, yeah.

Tanner Hardy (00:27:10):

Annoying little [inaudible 00:27:11] tag along.

Joe McCarthy (00:27:11):

Just kept doing that. And he kept responding to it. But he would move a little bit and move a little bit. And we just kept closing and closing and closing, moving on and step persistence. Don’t give up, pick a plan, go after it. Don’t be afraid to screw up. You screw up, you screw up. But the worst screw up isn’t doing nothing. And so in this case, we pushed and pushed and pushed and that bull finally had enough of it and it almost ran Shelly over it. She had to jump behind a tree because it was coming over some dead falls and it was a big six point. And so it’s jumping like a unicorn over these dead falls and it literally runs past her at three feet and runs right to me. And that’s just from that persistence, staying after it, staying with it. If you got the wind in your favor, stay with it. Make a plan, go after it. Don’t be timid and don’t just hang out.

Tommy Sessions (00:28:04):

Yeah. I’ve seen and I’ve heard multiple stories. I’ve had it happen to me is persistence is, I mean it’s the name of the game. If you’re not persistent, you’re for one, you’re not going to make it back out into the field the day after opening day or whatever. But two, it’s like you say, if you don’t stay on that bull, stay pushing a little bit. But to that point, is there too much persistence is can you push a bull past to where… I mean I know you can, but can you push even the most pissed off bulls that want to fight past their breaking point if everything goes in your favor except for him just taking off, run away. The wind’s good. Whatever. You think you can break-

Joe McCarthy (00:28:53):

I think, yeah, it’s all the different… I mean, every elk’s going to be different. Every scenario is going to be different. And that’s why we have multiple days to hunt. At some point, if you are pushing and you feel like you’re pushing him too far out, where at some point you’ve got to be looking at, I have now gone, I’ve walked in three miles, I’ve gone this elk, I’ve pushed him half mile or three quarters a mile. Am I getting too far out of an area where I can even retrieve him? And so maybe the next day you come back and you think about, okay, he was here, he’ll probably be there tomorrow and maybe I screwed this part of the thing up. Let’s try it by going over here. Maybe think about it that way and go, okay, let’s look at this and maybe rehash this and do it differently tomorrow. And so maybe you don’t want to push that elk out of there.

(00:29:45):

I mean, I don’t think I’ve pushed a lot of elk out of country. I don’t think so. I think it’s the same thing as people call them, call shy ducks. I think ducks can be called shy at times but ducks listen to ducks. Ducks, you listen to ducks sitting on the water when they call in ducks and that’s what they do. And elk do the same thing, depends on where you’re at, how much pressure they have. So maybe it’s an area that’s really pressured and I’m like, you know what, I will back off on this and back this. So it just looks, I look at it from a big picture, can I do better tomorrow? Is this my only chance I have with this elk? How much time do I have left in the season? And I weigh all that, try to figure out the pros and cons and just make a decision.

Bill Ayer (00:30:25):

Yeah, maybe talk about that a little bit because I think more and more elk are getting pressured by people. And then here in Idaho you got the wolves happening. So do you see any change in behavior? Because a lot of people like ah, there’s wolves up there that they all have gone quiet or there’s a bunch of people up there, they’re call shy, they’ve gone quiet. So what’s your thoughts on that? Do they go quiet or are they just calling differently?

Joe McCarthy (00:30:47):

I think they’re calling differently personally. I know that’s going to make a lot of people mad at me saying that, but I really think elk are vocal animal and they want to be vocal, they want to do their natural behaviors and I think it just changes the way that they act. Every time they throw out a location bugle or a big challenge bugle, they get pressured then hey, maybe I shouldn’t do that. Elk are a tactical animal. I worked on tac team and a couple of them. It’s that every step you take, you’re trying to make sure that you have the advantage and that elk are the same way. They’re constantly moving, trying to get the wind on you, trying to angle you, trying to see you before you see them. They’ll sit behind a tree and when they hear and if you bugle, when you bugle or you walk, they know exactly where you’re at.

(00:31:36):

I mean, I swear I think an elk could probably, if they could have a map, they could put it within an inch. They’re probably better than GPS. They can figure out. So they will move to a place where they can try to ambush you and see you coming. Again, that’s why I’ll try to circle, I don’t necessarily go straight out of elk. I’ll try to move left or right or something. Maybe even work the backside of ridge. It depends on if you’re hunting by yourself too. When I’m hunting alone, I do a lot of that. When I’m hunting with somebody, I do back off, I back off quite a ways and I will close the distance and then back off, close the distance, back off, close the distance really close, go up and over the hill and throw a bugle back down on the other side.

(00:32:19):

It looks like I’ve left and I make it look like I’m moving around, maybe push another elk doing other things. But my partner is down in front of me being still, trying to catch that elk moving that I am making noise. They know where I’m at and they’re going to try to move to get an angle on me, which when they’re moving now my partner can get an angle on the elk. And Shelly has actually done, I mean she’s phenomenal at being able to do that. She has had a lot of, she positions herself very, very well.

Bill Ayer (00:32:49):

Shelly’s your wife?

Joe McCarthy (00:32:50):

Shelly’s my wife, yes.

Tommy Sessions (00:32:51):

Yeah, I think partner hunting is definitely a luxury. Some people love to hunt solo, but I will say that partner hunting is a luxury. And if you can work together, it’s hard because there’s, as a partner or as a caller, you want to see the action and it’s really hard. You need to get that team like you’re talking about with you and Shelly, but where you as a shooter or upfront and you’re trusting that your caller knows exactly what you’re doing, but you as a shooter have to communicate a little bit. And what I’ve done in the past is little cow calls quick, fast, I’m moving forward or whatever because I like to say 60 to 80 yards of distance between the caller and the shooter if possible is ideal because then you can close that gap a little bit.

(00:33:43):

I mean, I’ve shot a couple elk at about, well one of them was eight yards and the others have been about 15. So it definitely works to get that distance closed. But that caller needs to trust that your shooter is in the right spot and not do the sneaky peak or whatever you want to call it, trying to peek over and look. And it can be a game ender if that caller is trying to sneak over.

Tanner Hardy (00:34:13):

So as the shooter, what are you trying to look for to set yourself up in the best case scenario or the best situation? Or do you and your caller talk about how you think this bull’s going to come in before you decide to split up and set up?

Joe McCarthy (00:34:28):

With Shelly and I, again, she’s my wife, so we talk a lot. And so we have, I mean now worked to the point where our communications almost-

Bill Ayer (00:34:35):

You talk to your wife?

Joe McCarthy (00:34:36):

Yeah. Well, sometimes she tells me where to go.

Tommy Sessions (00:34:39):

Hope my wife doesn’t listen to this. I don’t know. I’m just kidding.

Joe McCarthy (00:34:41):

But she’s pretty good at figuring that out. We’ve hunted with each other enough that we know where we’re going. My brother’s the same way. The group that he hunts with my son, again, we’re very close so we know how we work. I will, and I typically do, I will move back and then I come back and I try to get an angle on her to figure out where she’s at. And then I will move and I’m listening to that bull. So if she’s here and the bull is over here, and I’m standing here, I’m going to move over here. I keep doing this with that bull and I’m literally, because he’s hearing me and I’m trying to keep her-

Tanner Hardy (00:35:24):

Trying to keep a straight line between the caller-

Joe McCarthy (00:35:26):

I’m trying to keep-

Tanner Hardy (00:35:26):

… the shooter and the bull.

Joe McCarthy (00:35:27):

And she will sit and she will hold ground. Now she knows pretty well when to push forward. Now last year I think she was 12 yards from the bull and we just could not get, that bull would not give her a shot. It had high ground on her and it would move back and forth and I mean she could have taken a marginal shot. I mean angle wise she could have done that, but she didn’t, honestly, it’s just not worth wounding an elk. But we sat with that bull for an hour and a half. I mean, she sat at 12 yards with a bull for an hour and a half. And I was going back and forth, back and forth, raking, doing all this stuff and that elk just wouldn’t leave that bush. And she sat there and kept just, I mean it was a long time.

(00:36:09):

Finally the elk pushed, I pushed up and it backed up and then it looped around and went clear round behind us. We tried to get around on it, but then it winded us and it was over. But we will, and when you talk about distance, I think 30 yards is probably the max shot that I’ve taken on an elk. And that’s a lot. I mean, I’ve been hunting for a long time, made a lot of shots at three yards, seven yards. I’ve had elk with literally a friend of mine, Lance Sellers, he was sitting, he looking at the trail, it’s going across side hill and there’s big alder bush there and he’s going to sit by the alder bush and the elk’s going to go down the trail around the alder bush and it decides to go right through all the brush and literally stepped on his foot as he’s drawing.

(00:37:00):

And so the arrow hit the elk before the arrow actually cleared the bow. That’s the closest I’ve called in for somebody. But yeah, when it steps on you. And this is the funny thing with Lance. Lance and I have been friends for a long time, and so I hear the elk run away and I’m thinking, okay, he shot the elk and I go down there and he’s laying on the trail and he’s got his foot wrapped up in his sock and I’m thinking he shot himself in the foot. How do you do that with a bow? How do you even shoot yourself in the foot with the bow? I don’t even know how you could do that. And so I’m like, what you doing? And he’s like, the elk stepped on me. I’m like, what? Stepped on you? And he’s got a big bunion on that foot and he literally, the elk just took the skin right off the bunion and it was bleeding and he had his foot wrapped in his sock. But I was like, oh my god, he shot himself in the foot.

Bill Ayer (00:37:47):

Yeah. Talk about the setup a little bit more because in your mind when I first started elk hunting, you go down and you see a clearing ride, maybe a 30, 40 yard patch of clearing. You’re like, okay, I’m going to sit on the edge of this. He’s going to walk right out in the middle of this clearing and I’m just going to have a nice 20 yard pop.

Tommy Sessions (00:38:03):

Yeah, good luck.

Joe McCarthy (00:38:04):

They’re going to walk right to the edge of that clearing and they’re going to stay at that clearing and look across the way and they’re going to wait for you.

Bill Ayer (00:38:10):

Yeah. So talk about that, Tanner, I think you’re searching for that. Where does the shooter set up?

Tanner Hardy (00:38:17):

Yeah. Well, should you go through that clearing because he’s not going to come into it?

Joe McCarthy (00:38:20):

Yep. Go through it. And if you can work even, it depends on how big the clearing is and what little patches of trees you may have in there. If you can work the side of the clearing to where you can get him to come across that, where you’re better off to not be seen. Two years ago up there in the Sawtooth unit, we had a nice, it was a nice bull and he would come up and the cows would come up and walk right past my wife. I mean, we’re going to have cows going past her at seven yards walking past. And he would come up and call and he would make this big circle and the circle started at 80 yards. And then it was like it’s 50 yards. And she just kept slowly moving. As he would move down, she would get down further into a tree and we’re not talking big brush, we’re talking a little tree that you can just sit by and hold still.

(00:39:10):

And so we were waiting for the next pass and some other people came in and pushed them, which was interesting. These guys were very fit. They heard the commotion between me and the elk. And there was actually some other elk bugling, cows chirping. They had heard this and they were actually jogging into [inaudible 00:39:30] see these elk, which didn’t do well because they pushed it.

Tanner Hardy (00:39:32):

Were they hunters? They were hunters? Yeah.

Joe McCarthy (00:39:34):

Yeah. No, they were actually hunters. And I tell you what, I have all the respect for them.

Bill Ayer (00:39:38):

They jogged in?

Joe McCarthy (00:39:39):

They jogged in, they actually ran in.

Bill Ayer (00:39:40):

You’re not kidding.

Joe McCarthy (00:39:41):

No, they actually were running, they were down this ridge. And I’m like, what the heck? I mean they’re literally like, we can catch this. And anyway, I have a lot of respect for their fitness because they were trying to chase elk, which isn’t going to happen.

Tommy Sessions (00:39:54):

Lasso. He can style there, just hop on the back.

Joe McCarthy (00:39:57):

It was frustrating. It was like, what the heck? But anyway, that’s what she did. I mean, she’s moving this creeping up an extra 20, I mean there are 80 yards close, a little 15, close a little… If the elk’s going away and he’s looking back somewhere if he’s raking, move, because when they’re raking they got their head down and they’re doing this with the tree and they’re not looking at you.

Tommy Sessions (00:40:19):

And their eyes are closed too.

Joe McCarthy (00:40:20):

Yeah, a lot of times.

Tommy Sessions (00:40:21):

They have their eyelids closed because from what I understand, so they don’t scratch their eyes up and so their eyes are closed and they have a harder time hearing.

Joe McCarthy (00:40:31):

Make ground. I mean you can use that time. As long as they’re raking, make ground. I did that out of the St. Joe country, the elker bugle above. And that bull would get in smolder and rake and then there were dead falls that went through the alder. And I would get up on those dead falls and run the deadfall and then go to them run another deadfall and make ground like that. But every time he would rake, I would run. Not run, I’m trying to just run up the dead falls, but I’m closing that distance, 20 yards, 10 yards, five yards, seven yards, just creeping in closer and closer and try to where I can get, because he’s moving too. And I want that elk to move around and offer me that shot. So yeah, you’re pushing, trying to get as close as you can.

Tommy Sessions (00:41:17):

But it goes to Bill’s comment about, are they really running through the forests after these elk? If you hunt with me or hunt around me or see me hunt, and here’s some of the things I say are probably really stupid, but I call it the Mountain Olympics. When a bull bolt bugles, I go run and it’s to close distance or it’s to get a better, to try to outplay that elk and to get a better point if I got to run up to the top of the ridge or I got to run down to them, get to a clearing. Usually you get a bugle at the worst time possible when you have a bunch of nastiness in front of you and he’s 200 yards away and you’ve got this 50 yard patch of just zero shooting lanes and you’re like, crap, I got to get through that. Here I go. And you’re gaining ground and you’re just busting through that stuff.

Joe McCarthy (00:42:06):

I agree with that.

Bill Ayer (00:42:07):

Or the only way through is the run back out, up the hill, back down.

Joe McCarthy (00:42:12):

I think, you listen to elk. When elk run through the woods, they make noise. And it goes back to what you were saying too with the making noise. If you’re moving quickly, running, covering… I can’t, I’m just too old to run too far. If you can cover ground, you can cover ground fast, you’re actually going to sound more like an elk than if you’re going slow. I mean, think about the cougar, cougar’s stalking, stalking, stalking, stalking.

Tanner Hardy (00:42:38):

Methodical and slow and quiet.

Joe McCarthy (00:42:42):

And that’s with Bree’s Elk, that elk that followed us out to a running room. I mean, we just said now we’re done with him. And we just started out, and I think it’s just a fact. There was me, there was my wife, there was Bree, there was Cody, and we just walked out and we’re making tracks. We sounded like a herd elk like the bull that could come in, scooped some cows and he’s on the way out. And that bull that was down there, he started chasing us out. And so I think moving quickly has his times. The Dan Statons of the world up in Spokane, Dan has done a great job of putting out fitness things and I think the level of fitness of hunters in general is getting better. And I think there’s a time and a place to move quickly. But on the other side, you’re not ever going to chase an elk. I mean you’re just not going to ever catch them. That’s not going to happen. Especially when they’re stampeding and the dust is flying, it probably not going to work.

Tommy Sessions (00:43:36):

I will shamefully admit that I have tried not with an archery, with a rifle, and it was more to get a better vantage point, but within a matter of minutes the elk was probably four counties away and I would’ve never had a shot on him anyways. So it doesn’t matter. It’s if an elk bus and he doesn’t want to respond to you, it’s probably better to just head to the next drainage and go try to find another one.

Bill Ayer (00:44:00):

They’re not like mule deer. They’re not going to run to the top of the hill and look at you at 200 yards. They put two or three drainages between them.

Tommy Sessions (00:44:06):

Yeah, yeah. And they do it in 30 seconds.

Tanner Hardy (00:44:08):

And I think elk though, well that might be a mule deer later season. Hunt a mule deer early in the season, they won’t run 200 yards and look at you.

Joe McCarthy (00:44:15):

I think pressure though does tend to push elk will move farther and try to get away from pressure. So if you have elk that are pressured and that they are likely to move away and move into another drainage or move up to up the ridge and keep moving. When I lived up out of Latah County, out of Deary, we used to watch the elk and they had a three or four day cycle where they would start here and they would move to this timber patch and then move to this timber patch. And four days later they’re back in the timber patch right by the house. And I think elk do that trying to not necessarily hang out in the same spot.

(00:44:58):

And they keep themselves moving, doesn’t mean they won’t come back, but I think when you do break, when you do get busted in a bad way, like in this case with Shelly, when these people came running in, they were coming into us, they were actually coming into me bugling and they actually ran through the elk and which the elk didn’t like and the elk ran away. Once that happens, I think the game’s over, we’ve ended up finding those elk about three drainages and about a thousand feet higher in elevation and a day later.

Tommy Sessions (00:45:32):

Were they still, were those particular Elks still calling bugling? Were they were still hot and active?

Joe McCarthy (00:45:37):

They were still calling. Yeah, we found them. It was the next day, a little later in the afternoon we found them. But yeah, they’re talking. I just think they changed the way they talk. They may not always just let out that big challenge bugle, you may just hear that short little grunt or that little whine or that whatever. I mean, honestly you’re sneaking up on doing the tactical stuff. You’re trying to approach a suspect house or whatever. You’re trying to be quiet and you’re talking in sign language and you’re doing all this kind of stuff. Elks were doing the same thing. They’re going to be making softer bugles, maybe just little check bugles, little things like that. And they may not be blasting out, but that doesn’t mean that once you bust the bubble, that isn’t going to happen. Because once you-

Bill Ayer (00:46:30):

What’s the bubble for you? 80 yards?

Joe McCarthy (00:46:31):

Yeah, I think getting into 80 yards is pretty easy. You can pretty much get into 80 yards just by any elk without a whole lot of work. But inside that, I think it does get a lot harder because depending on where you’re at, the angles that the animal’s going to sit and he’s going to sit and look through those shooting lanes to find you. And so those movements you make at that range are more critical that they don’t see you. They’re going to do things trying to wind you, doesn’t take them very far to move. And they cover ground in a hurry to get behind you and you slip up and lose track of them.

(00:47:14):

It’s crazy how quiet they can be for an elk that makes, sounds like a stampede going through the woods all of a sudden they get super quiet and can smooth around on you. So that 80 yard bubble is kind of it. But I have no issues with bugling at an elk at full bugle at 10, 15 yards. I’ll scream at an elk right at them as long as I have some kind of cover or whatever and they’ll react. Once you get that bubble where you’re in close, it’s time to fight and that’s what you’re doing. You’re putting up the fight and trying to-

Tanner Hardy (00:47:50):

Do you find that it’s either one or two things when you do break the bubble, you bugle at them or whatever and they know that you’re within 80 yards, they’re either not into it and they’re gone or they’re fired up and hot and coming at you? Or do they play it any other way than that?

Joe McCarthy (00:48:06):

Yeah, no, they may be gone, but they’re not going to necessarily going to go. They’re not going to take off. I don’t think they’ll… I mean, there’s no rule that can’t be broken. There’s anything you say, there’s always going to be somebody that says something that can make it all make it wrong. But the reality is, you can keep dodging that elk, can keep staying off, stay with it and behind it, as long as you’re making good sounds and you’re not doing something to screw the elk up where he is like, oh no. I mean once they got your wind, you’re done. Once they see you, you’re probably done. So at that point you got to figure things out. And at sometimes too, those elk, you’re like, there’s no way they saw me and you move around and you go, yeah, no, he was right here. And I can look right through the trees and see just how he could see where I was at. And I’m like, son of a gun.

Tommy Sessions (00:48:59):

Well, if you put your binoculars up a rangefinder in the middle of the forest and you’re in the thick stuff, you’re like, why would I ever look through my binoculars? And you look at what you can actually pick out in 60, 80, 100 yards through binoculars. I mean, that’s what I’ve always equated what an elk or an animal period is going to be looking at you through is those binoculars through that forest. So I mean, you’re looking at that and you’re going, oh, that’s how they saw me. I moved this one foot or whatever it was, didn’t have a backdrop. And they busted me. They got me.

Joe McCarthy (00:49:30):

The wind, when you get into within 50 yards because winds go up and down and side to side and you just got all these things happening that you get this, which is great, and then all of a sudden, it goes right back to him. Now, it’s [inaudible 00:49:45]. Where that stuff really does play in. And when you cannot fight the wind enough. And as far as my camp goes, I used to, when I was younger, I swam pretty much every day in a creek, which is really, really cold. I have, since I’m retired and whatever, I have a shower, portable shower with a hot water heater that I run that I can pump right out of a creek and try to keep myself clean.

(00:50:12):

I do everything I can to stay as clean as I can. And even with that, they’re still going to wind you. So you do everything you can, but you got to that little puffer bottle reading that. It’s crazy watching that how it comes here and then goes down and then float and goes right down to where the elk is. And they will know those thermals and they will put themselves in those thermals sometimes more than they will their eyeballs. I think they trust their nose when they do their eyes.

Tommy Sessions (00:50:41):

Yeah, I’d say so. I think that just like if you talk about a wolf coming in or a cougar or whatever it is that’s coming in, I mean, they’re going to probably smell that animal far before they see it. And then at the same time, if you think about spotting and stocking an elk or an animal, you can get within five feet of that animal if you’re really good at spot stock. And until they get wind, they may be looking around, they can’t see you because you’re belly crawling or whatever it is. So I mean, that’s a prime example that wind is, I think they use that sense more than anything else.

Joe McCarthy (00:51:17):

And that’s where I think the call does play an advantage at some point in this, when you do get close, and it is not uncommon for me to be working in elk for two, three hours that I initially got the first bugle and it was three hours ago and I am now within 20 yards of it or 40 yards of it. And we’re still bugling and trying to ramp that elk up. There’s a point where elk get just like, I’m done. I’m ready to go kick this guy’s ass. I’m going to go shut him up. And I think in those cases there are times when he just had enough that you can get them to react and make that stupid mistake where they come across that clearing and they do that. So I think reading that animal and if you can get that animal pissed off where I am chuckling, I’m cutting him off, I’m bugling over the top of him, I’m grunting, I’m raking and I’m doing all that, peeing in his playhouse, at that point, they will make mistakes.

(00:52:22):

I mean, that’s where the elk walks in at two yards from you and stands there and he’s all pissed. And you could see they’re out of breath and they’re panting and they’re looking around. Their eyes are big and they’re checking everything out. And I mean, my wife’s sitting there at three yards from them, shoots them, boom down the go. So if you can piss them off enough, that works. Not all the elk do that. And not all the elk are going to be, like I said, I don’t think, not all elk are going to be call it, I mean shootable. I think, there’s some elk… They may be all, but we’re going to make mistakes. We’re human. That’s why I say keep making mistakes, keep going out there and push yourself. Make mistakes. Do what you can to try to do things. And again, don’t be afraid to bugle.

(00:53:09):

I am way more afraid of cow calling in close than I am bugling. Because when you start a read, when your mouth is, there’s a chance, there’s like a little sticky point. Once I get the read and running, then I feel good. But that first sound, I don’t necessarily want that first sound to be at 10 yards or 20 yards where he is like, what the heck? Whereas a bugle, you can screw a bugle all up and they don’t care. I mean, they just don’t care because it’s like, they sound like donkeys. They sound like all sorts of stuff.

Tommy Sessions (00:53:45):

Yeah. The bull that I shot a couple of years back, well, what was it, two years ago, in 2020. We nicknamed it Pontiac because it sounded like the belt of an old Pontiac Grand Prix squealing. And I can’t even reproduce that sound that elk was making. It’s because-

Tanner Hardy (00:54:08):

I think I know what it is. I have an old Buick at home that makes that sound.

Tommy Sessions (00:54:09):

Yeah, yeah. But this was Pontiac. It’s not a Buick. It’s different.

Tanner Hardy (00:54:13):

Oh, okay. Okay.

Tommy Sessions (00:54:14):

But they, it’s because they get so hoarse and they get to the point where they’ve bugled so much or they’re just that pissed off that they can’t control, it’s not the locate bugle, they’re just mad and they just let something out and that’s what it came out as. And so I think that goes to what you’re saying. A bugle can be so screwed up, but that’s what an elk sounds like. You’re not going to win worlds with it, but you’re going to kill a bull.

Joe McCarthy (00:54:40):

But elk too. And they get hoarse when that full moon comes out, whatever, and they’re out, they’re bugle at night and they’re doing that, they get wound up. And when their defenses, I think fall off at nighttime, they’re more aggressive to move around and show themselves a little more and they really get wound up. And as that happens, that full moon happens. You’ll hear those voices just go out where there is just nothing left in their voice because they’ve bugled a million times that night. When it comes to people start, when do you hunt? Full moon. Not full Moon. You hunt in September. You hunt September. You hunt as many days in September as you possibly can. And I have no issues with hunting in a full moon. I actually like hunting in a full moon. I get that when there’s a full moon, the elk will be up at night, they’re going to be all out.

(00:55:34):

And then probably right in the morning they’re going to probably be sliding off to their beds. And they may not be wanting to do something at 9:30, 10:00 in the morning. They’re going to get back moving again. And when you’ve had that night where you’ve had this big fight and from working patrol, you have a night where you get into a lot of stuff, that gets you amped up and you recall this adrenaline, they go back and they sit, but they’re thinking it’s still game time and they’re going to go. And I think those kind of times people overlook the full moon. Because I think there’s times that those elk actually get more wound up at night and I’d rather get that elk that’s all wound up than the one that is just playing around.

Tommy Sessions (00:56:20):

Sure.

Bill Ayer (00:56:22):

Yeah. So maybe talk about this. This used to be, or it still is, a lot of the times my nemesis, you get a bull going, you’re going back and forth. You’re working for about a half hour. You get within that 60 yards, 80 yards right there. You just need him to commit. But he’s got his 10, 20, 25 cows and he just continues to push them away. Continues to push them away and you follow him and follow him and eventually you lose him maybe an hour or two into it. He’s bugling up the hill and you just can’t go that fast. Yeah. What are some of the mistakes people are making that you think in that situation? Is there anything that you would recommend doing in that situation? You can only sound like so many elk. He’s got his little harem and he’s pushing.

Joe McCarthy (00:57:10):

I think that’s for throwing your bugle. So I like the idea of being able to sound like multiple elk. I think when you do that, and I have found that you can actually call a lot of cows in by bugling and when you sound like multiple elk in an area, so you throw a beagle off over here and then you throw a beagle off over there to bring and you can change those beagles up. It’s a little bit different. That makes it sound. And so you might get some, again, goes back to that street fight thing. Oh okay, they got this going on. The girls are definitely going to come to that as well. Again, don’t chase them straight behind him. I don’t necessarily tag right behind him. I try to loop either upwind or, I mean may want to go downwind of them, but you’re either going uphill or downhill depending on which way the wind’s going, where you’re trying to get on the side of them.

(00:58:00):

When it comes to elevation, I would rather not be above them. And I’d rather not be below them. I’d rather be side hill on them. I think elk come in a lot easier. It’s the same thing I found with turkeys. Turkeys when they are above you, they seem to have that high ground and they do a lot of getting the little perch and they’re down there looking for you, coming underneath you. I think again, in a lot of cases you get thermals that they’ll catch on that. But if you can get side hill to them to the same elevation, and then following that again, you got wind is important, but keep close. At some point you have to just say, hey, we’re good. But I think the biggest problem people have is they give up and people give up way too soon. And you need, like I said-

Bill Ayer (00:58:53):

I think that’s where I falter, is I’d rather give up and try to come back the next day and put a better plan on getting on them versus push too hard and then bump them. And so that’s where I always call it. And I always err on the side of not pushing, which I probably should push more.

Joe McCarthy (00:59:13):

Yeah. And my brother is the, he’s the king at being able to slide in and keep pushing. He’s aggressive and he goes after him. I look at that first bull that Cody killed when he was like 12 or whatever it was, we followed that dang elk downhill forever, it seemed. And I had given up. We had laid down in a burn and I’m just like, I am done. He is just worn me out. But Cody being 12 years old, he’s still on that bugle and he just kept bugling and bugling and bugling and bugling. And you know what? That bull had gone completely down to the bottom of this draw, crossed the creek and was up the other side.

(00:59:51):

And so he was literally on the opposite side of the hill from us. And I’m like, there’s no way we’re going to go get him. But he just kept bugling and sure enough that bull turned around and come right back. He walked through that burn with us. I mean, there’s nothing in the burn. We’re laying down, trying to hide from him. Walked right past us and he drilled it for his first elk.